How is this time different?

Lessons on the transformation of work

How is this time different?

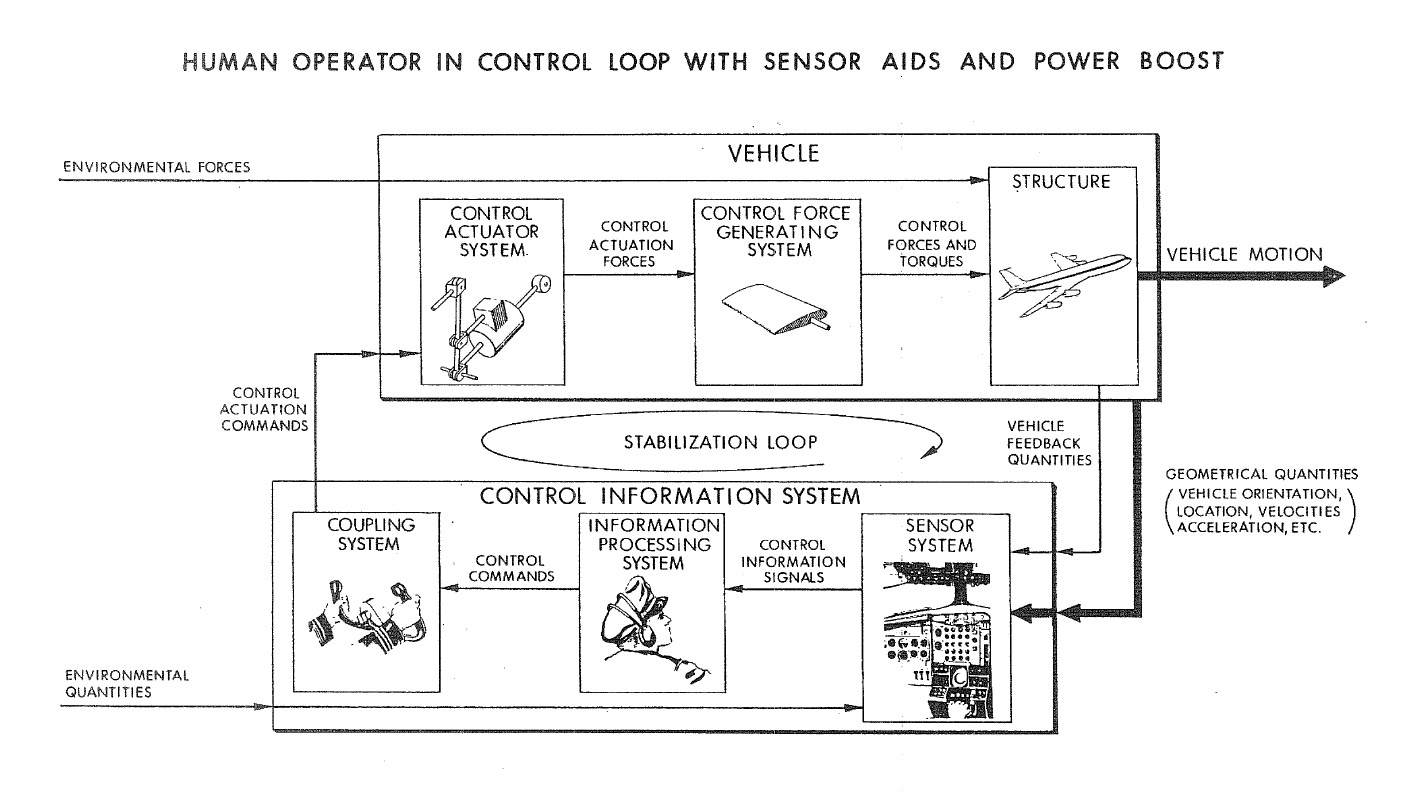

In the 1950s and early 1960s, breakthroughs in automation technology enabled leaps forward in safety and productivity across industries. Computerization during this period helped scale numerically controlled machines that transformed industry and autopilot navigation that dramatically improved the safety of air travel and transformed the role of the pilot. It was in this era that some of the first models emerged for how humans can work successfully with machines. Today, computing capabilities are radically different, but some of the underlying principles for how to design the role of the human in the loop are the same: configuring jobs so that employees can learn and improve; building and calibrating trust in the automated system; and managing the mental workload of workers so they are set up to succeed.

Our research has been revisiting these principles and trying to apply them to uses of generative AI. In 2023, our group at MIT began convening a group of companies to learn how they were approaching the adoption of LLM-based tools. We originally targeted a small sample of companies as a focus group, but soon we realized that far more companies were eager to share their experiences and learn from one another. We ended up focusing our research on approximately 20 companies and their experiments with generative AI.

Today, in partnership with Google, our working group is convening AI and HR leaders from more than 50 companies to reflect on the lessons from the first two years of generative AI in the workplace. At the event, we will present a summary of findings from our research and reflect on what we can learn from history. Here is a short summary:

Motivation

Our research had three objectives. The first was to understand how companies were using these tools, particularly the kinds of tasks and jobs that generative AI was affecting. Second, we were interested in how the adoption of generative AI was affecting the demand for skills within the workforce. Third, we were interested in how the adoption of generative AI compared to the adoption of past technologies, like personal computers, industrial robots, or robotic process automation software.

We had several hypotheses from the outset based on past experiences and early AI research.

Consistent with the adoption of personal computers, the internet, and software tools like Robotic Process Automation (RPA), the adoption of generative AI tools would be task based, not job based. What we have learned is that the uses of generative AI technologies are more flexible than past automation technologies, but less robust. That allows these tools to help with more tasks, while taking over fewer tasks.

The impact of generative AI on work would be less skill biased than past technologies. Early lab evidence suggested that generative AI was skill leveling as opposed to skill biased, but new evidence from software engineering and other domains suggests that area expertise is still relevant. The key question is under what conditions do these tools widen skills gaps as opposed to narrow them.

Effective use of generative AI technologies would require firms to undergo process transformation. This has generally been true. Although the dominant design of these technologies are not settled, process transformation has been required only in a subset of use cases. In others, there have been bottom-up uses that require workflow transformation at the individual level without process transformation at the team level. In other cases, generative AI technologies have been threaded within existing software systems that only require minor adjustments from the users.

Adoption would require a combination of process and technical knowledge. The adoption of AI tools seems to be motivated by trust and an interest in upward mobility, just as much as knowledge. Lack of technical knowledge seems to be less of a barrier to the adoption of these tools thus far. Successful adoption of these tools will require process knowledge, but there is a risk that process knowledge could be embedded in the tools over time.

The adoption of these tools could allow companies to leapfrog past gaps in their technology infrastructure, including gaps in their data infrastructure or use of prior automation technologies like RPA. We have not seen evidence of these tools allowing organizations to leapfrog critical investments in organizing critical data or understanding processes using these tools, although leapfrogging is a frequent appeal of these tools for organizations.

Based on research on generative AI in the lab and best practices from the field, we identify four central questions for organizations as they scale up their uses of AI:

How can organizations redesign processes and jobs to accommodate the strengths and weaknesses of AI tools?

When do organizations decide to develop and customize AI tools on their own, versus buy tools off the shelf?

How continuously do organizations experiment with modifying their AI applications, as opposed to fixing their processes in place?

How do organizations build in quality checks to interpret the results and recommendations that their AI applications provide?

Where is the impact?

As in the past, generative AI is transforming faster than organizations are transforming to use it. Even though these technologies have the potential to take on many tasks currently, the technologies still only work in pockets of organizations. Where there is breadth (e.g. company-wide chat tools), there is not depth. Where there is depth (e.g. customer service support bots, software engineering), there is not breadth. The shorthand is that half of the prompts for generative AI are coming from just 5% of the workforce. There is growing recognition that just because generative AI can perform certain work tasks, it does not mean that workers will use the tools for those tasks.

Academic studies of lab and field applications indicate significant productivity gains in several settings: writing, software engineering, and customer service.

Initially, our research had divided applications like these into three categories based on their intended outcome: productivity use cases that enhanced worker capabilities, decision support use cases that extended capabilities, and innovation use cases that created new capabilities.

As we saw how companies deployed these tools in practice, it became clear that applications did not always neatly fit into these boxes. Many use cases could fit into multiple categories based on how the technologies were integrated into a workflow.

Consider customer service applications. There are multiple ways that generative AI has been used to change the way that customer service organizations manage inquiries. In one model, a LLM-enabled chatbot can handle customer inquiries mostly autonomously, elevating certain questions based on customer feedback to human customer service representatives. In this model, the generative AI tool is enhancing productivity without providing decision support.

In a second model, where customer service agents are often charged with responding to technical questions about a product, the LLM-based tools are integrated to give customer service agents the relevant knowledge to respond to customer questions. The purpose of these tools is to help individual customer service agents without prior expertise in the customer’s question to extend their capabilities and allow them to handle a broader range of questions accurately. The benefits are higher-quality responses and a faster learning curve for new customer service representatives.

There are similar examples for applications of generative AI in software engineering and writing tasks, where the impact of the technology depends on the way that the tool is integrated and the human worker’s job is redesigned.

How did organizations decide where to start?

Based on how companies introduce new software tools, we expected a mix of top-down introduction of generative AI tools (beginning with CFO and CTO approval), as well as a call for bottom-up input of how the tools should be used.

The potential difference with generative AI tools was that they are available as consumer tools as well as enterprise tools. Therefore, companies had less control over the bottom-up uses of the tools. In some cases, companies in our sample felt pressure to adopt the tools at an enterprise level because they assumed that their employees would be using the tools anyway. And they wanted their employees to use the tools safely. This dynamic accelerated the pace of adoption and weighted the pattern of adoption toward bottom-up use cases.

Nonetheless, we saw heterogeneity in the approach across our sample. There have been both bottom up and top down approaches with clear tradeoffs. More risk-tolerant and experimental organizations have supported bottom-up approaches. More risk-averse organizations have focused on top-down accountability.

Each approach has clear tradeoffs. Top-down approaches to technology deployment have had difficulty scaling, partly because the work that generative AI tools seek to augment is often non-standard, and scaling up generative AI tools requires workers to buy in and change their job roles. However, top-down approaches often benefit from clear metrics for success and potential impact on a business process.

Since early adoption of generative AI tools has been decentralized, bottom-up approaches benefit from an existing user base. The typical bottom-up approach is to enable employees to make creative use of generative AI tools, then identify the highest-potential use cases. This approach has achieved broad adoption, but the value of this adoption is hard to quantify – and it is not clear how this adoption can lead to deeper, more valuable uses that enhance productivity.

How did organizations motivate adoption among workers?

One of the findings from our “Automation from the Worker’s Perspective” study was that trust is a key predictor of how workers perceive new technologies like AI. Using the same data, our graduate student Marilena Bellonia found a strong association between reported uses of AI and levels of trust. One challenge for motivating adoption is calibrating trust.

We have noticed two approaches to engage with workers. One begins with early adopters and tests potential use cases with these workers, who often have the highest trust in AI tools and the highest motivation to work with them. These workers also may have different work habits and ways of completing their tasks than their peers. What works for these workers may not work for others. And even if the workflow might be generally applicable, there is still the challenge of building trust with the next segment of the workforce.

In one use case we studied, a large business services company built a decision support tool for their sales team working with their top performers. They went through a typical process of user-centered design, gathering feedback from the top performers to inform what data the tool would include and how it might be used. But when this company tried to introduce the tool that had been designed for their top performers to the entire workforce, there was low adoption.

In response to this challenge, we have observed an alternative approach where organizations begin by building their AI applications for the most skeptical workers. The hypothesis is that if you can win the favor of these workers, you can win over anyone. Although we do not have clear evidence of starting with skeptics being a better solution, the primary takeaway is that different workers are going to be motivated to make use of AI tools for different reasons – and one approach to adoption is not going to fit all.

Our survey research found that what workers want out of their job can be strongly related to their perceptions of automation. For example, workers motivated by learning and career growth are more likely to embrace technology, whereas those workers for whom money is a primary motivator are no more likely to be optimistic about new technologies.

How do you measure success?

In the beginning of our research, companies were focused on measuring the value of generative AI by its labor savings, similar to how companies measure the impact of automation software or industrial robots. However, it soon became clear that this focus on labor productivity alone was incomplete. Often labor productivity is hard to measure and connect to the bottom line: an individual’s ability to complete a given task more quickly does not necessarily save an enterprise money – or help it earn more. And even if a given worker saves 20% of their time, these are often “soft savings” because employers always productively reallocate 20% of that worker’s time right away.

The search for productivity gains has led to a fascinating evolution in how the companies we have studied talk about the value of generative AI for their companies. In some cases, companies continue to chase after productivity gains. In other cases, they are focused on developing new capabilities.

The most promising use cases of generative AI that we have identified are focused on addressing a longstanding problem for a company that previous technology tools were not able to address. For example, in healthcare, note summarization was a longstanding pain for doctors that they were motivated to solve, but that previous softwares made it labor intensive to do so. In law, due diligence required painstaking review of phrases with slight differences to categorize contracts. In both cases (and others), generative AI tools unlocked a new capability to address a problem that workers already understood and were motivated to address.

Design for Learning

There are three primary ways that automation can fail: disuse (not automating when adding new technology could be beneficial), misuse (deploying automation technologies with poor results), and overuse (the automation technologies work well, but they lead to unintended consequences). The applications of generative AI that we have studied are vulnerable to all three, but there are ways to guard against them.

For disuse, the problem is low adoption of tools that could be beneficial. This could be a challenge of building trust, or a problem of risk aversion: organizations may not want to change a process that is working. What we found in our survey of workers is that the more a worker sees their employer as invested in them, the more optimistic they are about the impact of new technologies. It’s possible that building trust in new technologies may require trust in the people who are deploying them more than a change in attitude toward the technologies themselves.

For misuse, the problem is sometimes that there is a mismatch between the technology interface and the people trusted to use it. Various studies of the impact of radiology in AI highlight how – for some radiologists – access to AI tools does not substantially improve their performance, compared to the AI alone. The solution here can be reconfiguring the role of the human to emphasize their skills and account for their biases. In some cases, this may mean choosing a lower level of automation than is possible to ensure that the human in the loop is engaged in the process and building their expertise.

For overuse, the challenge can be that automation is working so well that the process becomes rigid and stops improving – or the people involved cease to develop their skills.

There is early evidence of cognitive and organizational tradeoffs associated with generative AI tools, just as there have been tradeoffs with the adoption of previous technologies. Recent studies have linked generative AI use to lower recall of relevant information, and in our research, we found concerns about loss of teamwork and skill atrophy. When tasks become concentrated around one “human in the loop” rather than a distributed team of experts, there could be downstream consequences for mentorship and innovation. Moreover, when an expert is interpreting data from a LLM rather than generating new information on their own, it could reduce their rate of learning – and limit their organization’s ability to innovate.

The antidote to this challenge is to design systems with generative AI where a key priority is the learning and improvement of the humans in the loop. Workers using generative AI for software engineering report that they are sometimes developing a program without really knowing how they are building it. Technical specialists in finance and healthcare are using LLMs to synthesize information from various fields without the opportunity to reflect on where the information came from or how it could be improved.

Consider the example of an IT organization of a large corporation that was traditionally organized around the company’s functional tools. For example, there were IT experts who specialized in the CRM, in the company’s cloud tools, and other software. When the IT team started using generative AI, they could have used the tools to automate the routine tasks for each tool. Over time, that process might have risked skill atrophy or process rigidity because the problems that each domain expert addressed would have become narrower and narrower.

Instead, the IT team reorganized so that their experts could respond to the highest priority problems of the business as they emerged, whether they were specific to one software tool or cut across the whole system. The concept was that the IT personnel could become problem-solvers, and generative AI tools could extend their capabilities into new domains to help them solve problems.

We know that workers who are motivated to learn and grow in their careers are likely to be more optimistic about new technologies. It is also important that the design of new technologies is set up to help workers learn and grow in their careers.

When considering AI, I feel compelled to share this article. I believe it is deeply important and would love feedback from the intelligence collected on this page:

https://open.substack.com/pub/justinhewitt42/p/the-ground-beneath-the-sky-teaching?r=4aa574&utm_medium=ios

Well I'm simply looking at how AI can expand my learning and enhance my life.